The catastrophic effects of climate change continue to wreak havoc on Europe and the world. We witness more frequent floods, droughts, and extreme temperature events, underscoring the urgency of bringing down greenhouse gas emissions. In addition to its devastating impacts on the environment, the past few years have shown how fossil gas can be weaponised, threatening energy security and burdening EU citizens with energy poverty.

As politicians gear up for the 2024 European elections, it is imperative that combating the climate crisis by transitioning away from fossil gas becomes a top priority. The forthcoming European Parliament and Commission must ensure the continuation of the European Green Deal and take measures to significantly reduce energy demand while promoting renewable energy, flexibility, and circularity. Most importantly, they must set the political agenda for phasing out fossil gas in a fair and just manner by 2035.

The following paragraphs provide an overview of the dangers of fossil gas reliance and the ongoing political developments. In addition to this contextual piece, NGOs have developed a detailed “10 Point Plan For A Fossil Gas Phase Out” to guide the framework needed to achieve a phase out by 2035.

Why is fossil gas reliance dangerous?

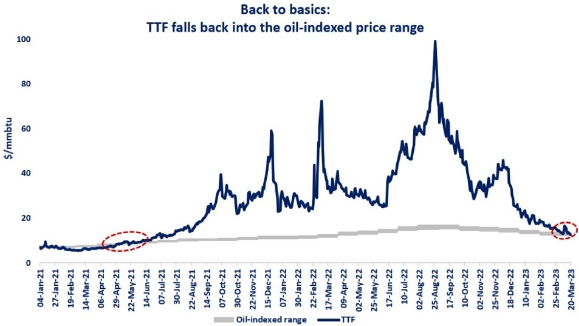

The challenges posed by the post-pandemic economic recovery in 2021, coupled with the energy crisis and the need for alternatives to Russian gas, have resulted in a cost-of-living crisis. Consumers have been hit hard by high price volatility, with gas prices skyrocketing from 18€/MWh before the crisis in January 2021 to a staggering 341€/MWh in August 2022.

This rollercoaster ride led to an almost twentyfold increase in prices. Although prices have somewhat normalised at around 25€/MWh in early June 2023, consumers remain highly exposed to the extreme price volatility of gas, as shown by the recent decision of the Dutch government to permanently shut down Groningen extraction fields in October this year, resulting in immediate price spikes of 30%.

Liquefied natural gas (LNG), a major substitute for Russian pipeline gas, is not only more expensive but also more polluting than piped gas. Several other factors including export facility shutdowns, increased price competition from China’s economic revival, and weather-related events like cold winters or droughts and extreme heat in the summer, could contribute to further gas price hikes in the coming years. Hence, despite recent price reductions, consumers still face significant risks associated with volatile gas prices.

Source: TTF prices fall back to the oil-indexed price range, March 2023

Significant gas demand reduction is possible: Member States have shown it

As a consequence of the changing geopolitical situation and high price volatility, the EU unanimously decided to move away from Russian gas, projecting to reduce imports by ⅔ by the end of 2022. According to the IEA, this objective was overachieved, with the share of Russian piped gas imported to the EU dropping from 40% in 2021 to below 10% by the end of 2022. However, out of the 400 bcm of gas consumed in the EU, less than a quarter (100 bcm) still comes from Russian LNG and piped gas imports between January and November 2022.

Recently, Member States decided to extend the 15% gas demand reduction objective (60 bcm) until March 2024. Initially, this temporary emergency measure applied from August 2022 onwards to ensure full gas reserves for the winter season. Member States overachieved and gas demand went down by almost 18% between August 2022 to March 2023. A recent Hertie School report found that Germany, one of the largest gas consumers in the EU, witnessed a 23% decrease in consumption across households, industry, and power stations in the second half of 2022. An even bigger decrease, which was not only due to weather fluctuations.

The emergency gas demand reduction measures have demonstrated that Member States can reduce gas demand in a short period. The largest reductions have been delivered by buildings and industry, through a mix of awareness raising campaigns and measures to reduce heating and cooling. Some of these savings were ‘no-regret’ measures with no draw-backs, such as turning off lights at night. A quarter of the reductions were achieved through structural changes, such as renewable energy and energy savings, while another fraction represented temporary developments such as production stops, mild winters, or rising energy poverty and unaffordability.

Gas demand reduction measures should certainly be pursued, made legally binding and decoupled from crisis situations. They should focus on developing further structural renewables, efficiency, and energy demand reduction measures as they will help to relieve consumers from volatile gas prices. It is crucial that these measures protect and prioritise vulnerable customers, prevent growing energy inequalities, and ensure citizens can benefit from the energy transition.

The Gas – Exit is in motion

Beyond these emergency measures, efforts to phase out fossil gas are already underway, with specific legislative pieces like the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and the Energy Efficiency Directive leading the charge. Under the EPBD, in particular, the European Parliament excludes subsidies for gas boilers from January 1, 2024, and aims for fossil-free buildings by 2035 (or latest by 2040). This significant development is especially noteworthy since buildings account for 35% of gas consumption in the EU. Additional rules banning sales of ‘stand-alone’ (non-hybrid) fossil fuel boilers by September 2029 are being developed under the Ecodesign Regulation for space and water heaters.

Ten countries in Europe have made plans to ban the installation of new gas boilers in new and/or existing buildings. For instance, The Netherlands will ban new 100% fossil boilers in all buildings from 2026 onwards (with a non-neglectable caveat, however, for hybrid heating systems i.e. hydrogen boilers or heat pumps).

The Commission’s REPowerEU plan, which aims for increased ambition in renewable energy and energy savings while moving away from Russian fossil fuels, sets the stage for a significant reduction in EU gas demand. The 2030 Renewable Energy Target has now increased from 32% to 42.5% and the EU has, for the first time, a binding energy efficiency target that increased from 9% to 11% (compared to 2020 projections). Member States have also agreed on faster permitting procedures. Therefore the implementation of the planned REPowerEU measures would result in an estimated EU gas demand reduction of 52% or even 67% by 2030.

Industry can take on the challenge

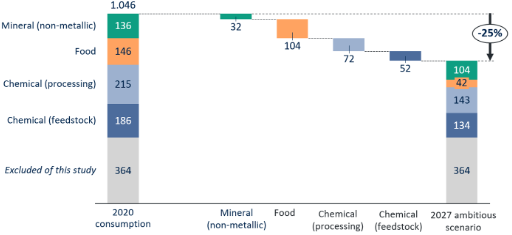

A closer look at the industry sector shows its great potential for gas demand reduction. Especially low temperature heat sectors such as food can achieve cost effective gas demand reductions (in terms of investment and fuel costs) by switching to heat pumps. Chemicals, food, and glass & ceramics contribute to ⅔ of the EU industry’s gas demand. Implementing all available alternatives in these sectors could help reduce up to 25% of the total EU industry gas consumption in the next five years. Direct electrification with renewables remains a viable and necessary solution for several high temperature processes.

Source: Opportunities to get EU industry off natural gas quickly, Climact, 16/05/2022

Similar results have been found by Agora’s recent Gas Exit report as fossil gas demand in the industry is largely reduced in the medium and low temperature sectors through efficiency measures and direct electrification of heating processes. By 2030 gas demand will decline by 54% in mid temperature steam production (100-500°C) and by 50% in low temperature space heating and cooling (below 100°C) sectors (compared to 2018).

Conclusion

Politicians now have a golden opportunity to establish a clear trajectory for an EU-wide fossil gas phase out. Over the past 18 months, significant progress has been made in this direction, and it is crucial to maintain the momentum. Such a move will not only strengthen Europe’s leadership role in the fight against climate change but also guarantee peace, energy security, and protection from energy poverty for European citizens. Moreover, it will provide investment security for industries by offering affordable and secure energy sources. An EU-wide gas phase out, backed by sufficient funds for a smooth transition, will yield multiple economic benefits for people, the planet, and businesses.

With the coal phase out nearly accomplished, the next urgent step – as civil society organisations call for – is to develop a well-structured, EU-wide plan to progressively shift away from fossil gas by 2035. By doing so, we can ensure a greener and more sustainable future for all.