COP27, hosted by an African Presidency, is here. Judging its outcomes will not only depend on the negotiation agreements and in the form of COP decisions, and to what extent these will deliver progress in key areas that CAN Europe has stressed as essential, such as mitigation for 1.5°C, adaptation and loss and damage finance. What matters as well is that, the EU does not enter into ‘panic shopping’ new fossil fuel exploration and purchasing deals with African countries or extending fossil gas infrastructure, risking thus to torpedo the EU’s energy transition and to lock-in Africa in fossil fuels. Signing new gas deals at an international climate conference would be very alienating if not the apogee of hypocrisy.

The energy crisis that was kickstarted with Russia invading Ukraine, has exposed that Europe has a problem with fossil fuel dependence. Although the Commission’s ‘REPowerEU’ plan was a right step forward, it failed to propose how to put a quick end to the EU’s fossil fuel imports from Russia, nor to phasing out fossil fuels in general, and it got Europe dashing for diversification towards many parts in the world, including Africa. The EU’s strategy was set to replace the 155bcm of Russian gas imports by new deals with the US, Qatar, Azerbaijan, and Africa.

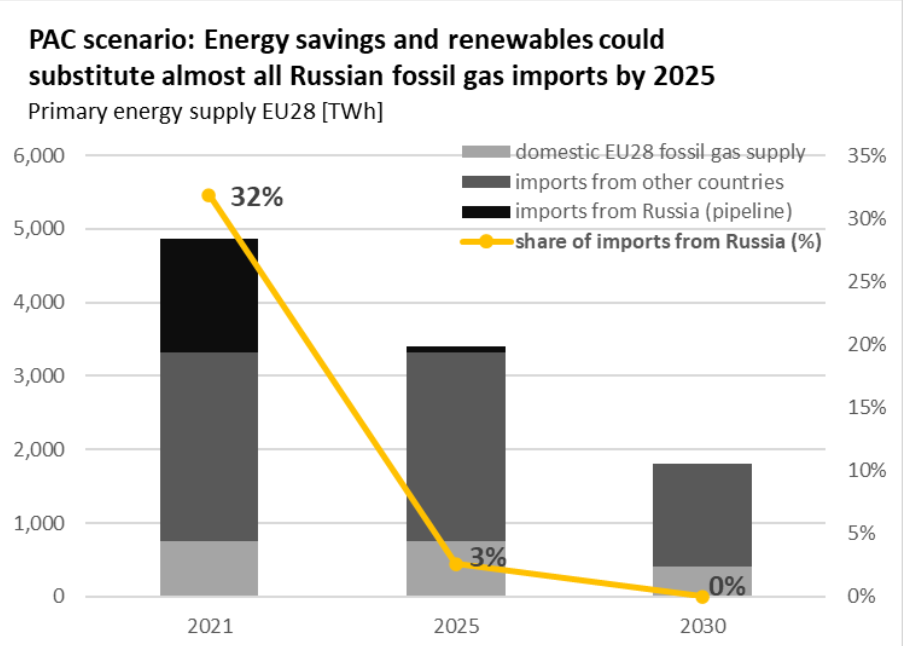

The findings of CAN Europe’s Paris Agreement Compatible (PAC) scenario show that a strong reduction of fossil gas demand is indispensable for the EU to live up to its commitments to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C. Provided that the PAC scenario pathway is implemented, the slump in fossil gas demand by 2025 is huge. It equals roughly the total amount of fossil gas imports from Russia to the EU28 in the year 2021.

With skyrocketing energy prices, soaring inflation, and the looming climate crisis, the EU should not undermine its climate objectives and the continent’s efforts to more rapidly move to energy savings and renewable energies. This has been loudly voiced as a demand by a large group of African civil society organisations through the “Don’t gas Africa” campaign, who want to send a signal to their own governments, and – with the letter released on 2 November targeting specifically European leaders – that the EU’s hunger for gas should not lock-in Africa into fossil fuels.

Africa at a crossroad

Africa is facing huge challenges in addressing energy poverty while securing a just transition away from fossil fuels in some countries, and in others leapfrogging fossil fueled development altogether. Africa can become a clean energy leader with decentralised renewables powering a more inclusive society and a greener economy, or it can become a large polluter that is burdened with centralised energy systems and future stranded assets.

Last year, the International Energy Agency said that to reach net-zero emissions globally by 2050 no new oil or gas fields should be approved for development, if the pathways should be consistent with the Paris Agreement. At the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, Germany and other EU countries pledged to end international funding for unabated fossil fuel projects by the end of 2022.

At COP26 also a new acronym emerged, JET-P for Just Energy Transition Partnerships. Such a cooperation with South Africa was launched, with indicated support by Germany, France, the UK, the European Union via the European Investment Bank (IEB), and USA a few developed countries in the order of 8.5bn USD to assist in the planned coal phase-out. There seems to be a high likelihood that COP27 will see a more detailed announcement of this partnership. Some updates (e.g. by UK & South Africa, and Germany) have been made available publicly recently which allow to track progress to a certain extent. While probably each JET-P will have to have its own parameters, due to different national energy circumstances, it can be expected that it will provide guidance and inspiration for other partnerships.

To act as a successful model, the financing needs to follow principles of equity, include scaled-up contributions from wealthy countries, and be sensitive to indebtedness of South Africa and the involved companies. Recent leaks of information have indicated financing is on the wrong track with only 2.7% of climate finance as grants and a high share of non-concessional financing. All partnerships should adhere to strong standards of inclusiveness, participation and human rights protection, which will serve their success in the long run.

The fact that South Africa’s climate plans are among the more ambitious ones according to scientific analyses such as that of Climate Action Tracker may be conducive for a comprehensive support package. It will of course be important that it matches key climate criteria – no fossil fuels, but full focus on renewable energies – as well as aspects of a “just” transition, serving people’s energy needs.

In addition to coal-heavy countries like India, Indonesia and Vietnam, Senegal is mentioned under the JET-P label. Late October, French and German delegations were in Senegal for further considerations of such a partnership, but whether real progress will be announced at COP27 remains to be seen. Overshadowing this is the potential role of Senegal as a supplier of fossil gas and LNG to Europe, partially to substitute Russian gas, which has received particular attention from the German government – and specifically its chancellor Olaf Scholz – as some statements and reports around the G7 summit in June indicated. While a JET-P itself, if fossil free, could become a transformative tool for Senegal’s energy sector, just promoting fossil gas in a side deal, formally outside of the JET-P, would be really damaging to Europe’s own climate credibility, even if technically the resources invested might not come from official development assistance, or specifically climate finance.

Of course, the EU’s cooperation with Egypt as the host of COP27 will be under a particular spotlight. Egypt submitted its first update to its Paris Agreement target in July 2022. Climate Action Tracker (CAT) rated it as “highly insufficient”, a very negative rating underlining the incompatibility with the 1.5°C limit. In its analysis, CAT specifically mentions that “Egypt is scaling up its domestic fossil gas production and use, risking locking itself into a high-carbon pathway.” In this situation, ahead of COP27, there are clear signals of an intensification of the energy cooperation, but with some concerning attention to fossil gas. In June, the EU signed a trilateral MoU with Egypt and Israel which focuses on the stable gas supply, and the references to the Paris Agreement, to the EU’s carbon neutrality goals, “green energy” and hydrogen rather read as a side note (or lip service?). The levels of investment associated with the MoU remain unclear. However, a clear prioritisation of renewable energies and efficiency, including green hydrogen are essential.

Renewable hydrogen?

COP27 will serve as a platform to officialise green hydrogen partnerships (through a MoU) between the EU and Egypt but also the EU and Namibia. It remains to be seen if those MoUs will include green renewables based hydrogen only or also present a platform for fossil gas. EU Energy Commissioner, Kadri Simson, travelled to Algeria mid October to discuss increased gas extraction for imports into the EU. Other partnerships for increased gas exploration (EU – Algeria or Italy – Angola), increased LNG supplies (Germany – Senegal), or others in Nigeria, Mozambique might be announced as well.

Hydrogen is misleadingly considered the new transition fuel (after fossil gas) as it is seen by many as a clean alternative. However hydrogen production is far from being fully renewable, while the gas industry pushes for existing or new infrastructure, creating stranded assets and fossil gas lock-in. The EU must not use public funds for new gas, LNG or so called hydrogen ready infrastructure nor extraction projects (including through the Recovery and Resilience Facility, the financial leg of the REPowerEU etc). The vast majority of renewable hydrogen must be produced domestically in Europe. If renewable hydrogen was to be imported to help the nascent renewable industry, this can only be the case if:

-

The exporting country has full energy access and has embarked on the energy transition

-

Additionality is guaranteed

-

Robust sustainability criteria are in place to support a nascent renewable energy industry

Ahead of the February Africa EU summit this year, a joint CSO statement, which CAN Europe joined, highlighted that Africa’s situation deserves extraordinary attention as it contributes just 4% of global total greenhouse gas emissions (with more than 17% of the world’s population), yet its development is threatened by the climate crisis, and facing huge climate adaptation challenges and increasing losses and damages. The undersigning organisations called on African governments to pursue a development-centred approach to climate and energy goals, which respects African-ownership and community and civil society participation, but focuses on the continent’s abundant renewable energy potential. This provides great opportunities for driving a broad socio-economic evolution towards a green economy with an African-based sustainable and resilient value chain.

In a time of constrained resources and climate crisis, there is no place for public financing for fossil fuels. On the basis of climate justice and capacity to transition, the EU, African countries, and financial institutions should rather work out ways to accelerate phasing out all fossil fuel finance, including through direct foreign investment, official development assistance, support from bi- and multilateral development banks, and export credits. There should be support for the development of financial environments and policy frameworks that provide sustainable investment, with a special focus on small-scale actors. Accessibility of funding and capacity to pay for renewable energy technologies remains a major challenge for the majority of communities and small enterprises in Africa. The structure of financing must therefore be improved, with greater attention paid to the development of direct financial access opportunities to small- and medium-sized renewables projects through adequate and appropriate financing and risk-taking instruments.

COP27 will be a test for Europe’s credibility as a climate leader. The EU should not achieve its emission reduction targets and energy security at the expense of outsourcing its energy transition to vulnerable countries, which face the biggest impacts of climate change [read report on Africa-EU partnership through action on climate impacts] and might not yet have achieved a switch to energy savings, efficiency and renewable energy for their own domestic needs. Instead, the EU should more quickly reduce its reliance on fossil gas use overall, and fulfil its obligations to massively increase support for its African neighbours by accelerating the financing and use of renewable energies, as envisaged in many African climate mitigation objectives (NDCs).